A Major Country Hopes A 4 Day Work Week Will Help Its Unpopular Reputation

Despite the U.S. having one of the worst work life balances among developed nations (complete with underutilized vacation, longer worker days, and excessive amounts of burnout among workers) there is one country in particular where employees regularly clock even more hours than U.S. workers — Japan. A 2022 survey from Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Labour Standards Bureau found that roughly 10% of Japanese workers worked more than 80 hours of overtime per month. This excessive culture of overtime not only affects the country's birth rate (which has been steadily declining for years) but places workers at risk for something known as karoshi or death from overwork. In fact the government survey found that 1 in 5 workers was at risk of karoshi due to the potential for stroke, heart attack, or even stress-induced suicide.

However, despite this long standing overworked reputation, Japan has been working to lessen its overwork culture. According to data from Clockify, the average annual working hours for Japanese workers declined 10% between 1980 and 2022. For comparison, the U.S. has only experienced a 5% decline in that same time period, which means workers in both countries now have fairly similar average working hours every year. However, while U.S. companies have pushed hard to force workers back into the office, Japan is actively working to correct and improve its unbalanced work life culture (and, hopefully, the birth rate at the same time). Most notably, they recently introduced a four-day work week.

Japan's new policies

Chief among the country's motivations is its declining birth rate. Japan's birth rate hit a record low for the eighth year in a row in 2023, with women averaging just 1.2 children in their lifetime. Related to the birth rate is also the country's marriage rate, which also continues to fall (the number of marriages dropped 6% in 2023). While the country has previously increased subsidies and parental leave offerings for workers, critics argue that the majority of the government's previous measures targeted already married couples intending on having children rather than the fact a growing number of people simply aren't getting married at all, let alone having children. This is part of why the government has decided to try its new four-day workweek approach.

Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike announced that beginning in April 2025, metropolitan government employees will have the option to take three days off each week (for a four-day work week). She went on to explain, "We will review work styles ... with flexibility, ensuring no one has to give up their career due to life events such as childbirth or child care." This policy is especially significant for women in the country, who still face strong cultural expectations to choose between a career or having a family. This is exasperated by the fact that Japan also has one of the worst gender gaps among high-income nations with just 54.9% of women participating in the workforce compared to 71.5% of men, according to data from the World Bank Group.

What's next for Japan

Without a significant increase in the birth rate, Japan's population is projected to fall by about 30% by 2070. To further complicate this, of the remaining population at that time, four out of 10 will be over the age of 65. So, while the Japanese government might hope that its four-day work week offers workers more downtime to get married and have children, its plan might not happen fast enough. Plus, it's debatable how much changing the work-life culture of the country will ultimately affect the birth rate. Takahide Kiuchi, an executive economist at Nomura Research Institute, explained to AP News, "Simple economic measures such as increase of subsidies are not going to resolve the serious problem of declining births."

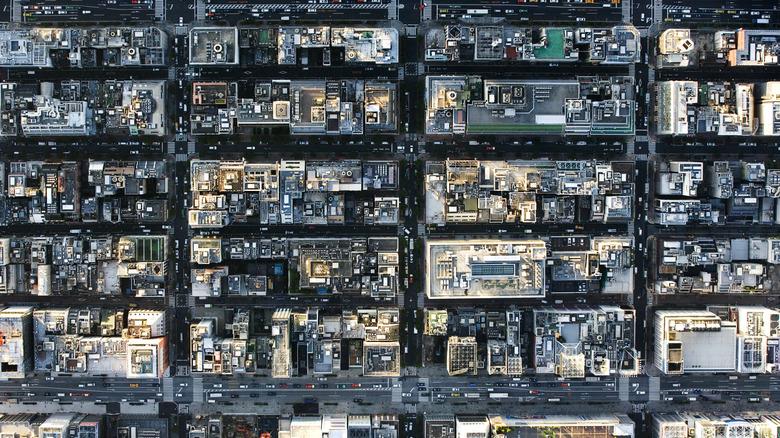

According to NHK World News, among the most common responses to a Japanese government survey, people reported that finances (having a baby is more expensive than you might think) and struggling to balance their work life were significant obstacles to having children. Other barriers include less-than-stellar job prospects, which pushes more young people to move to Tokyo, and the subsequently high cost of living required to live in the city. It's worth noting that, of Japan's 47 Prefectures, Tokyo has the lowest fertility rate (at just 0.99 children per a woman's lifetime) but has the highest population with over 37 million people living in the metropolitan area. Gender-biased corporate culture is another significant issue for women in Japan, where they face additional obstacles to having children through the fear of losing their jobs.