11 Ways The US Economy Is Designed To Make The Rich Richer

American economics are a strange hodgepodge of policies that don't immediately seem to jive with one another. On one hand, there's the school of trickle down economics that suggests tax breaks and enhanced financial opportunities for high earners will stimulate the economy from the top down. On the other are direct stimulus payouts that rejuvenate the marketplace by infusing consumers with direct buying power.Each has been hallmark legislative staples of both major parties throughout the years. Aggressive tax cutting policies (combined with targeted hikes) remain a primary feature on the campaign trail for this year's presidential candidates, as well.

The idea of trickle down economics was always a loser. It never infused the economy with enhanced spending power, and only served to make the rich more well-endowed. Rae Deer, writing for Jacobin, notes that the policy has "always been a scam," with "the impact of tax cuts for the rich [having been] clear" for some time. The Washington Post equally reports that data covering a 50 year period shows evidently that lowering taxes on the wealthy increases inequality on the whole and offers "no value to overall economy." If this is the case, why is it that this mode of thinking still pervades American fiscal policy? The short answer is that the US economy is slanted in favor of the rich, often directly at the expense of everyone else. Here's how it works.

'Who benefits from practices that keep people poor?'

Anyone contemplating the current state of the American economy should consider the natural dichotomy of outcomes. It's this topic that Matthew Desmond discusses in "Poverty, By America." Namely, it's crucial to ask who benefits from the parameters of the current system. Everything related to the political machinations of a place ultimately boils down to the people who craft policy. Sometimes it can be explained by a victory of their better angels, but often times it's a reflection of personal experiences, natural biases, and of course, their preferences, assumptions, and a healthy dose of self-service. Simply put, the people who craft policy for the rest of us often choose to do things that benefit them.

Politicians are elected to make tough choices in order to serve their constituents, but the reality is that there's no equivalent fiduciary duty involved in political office. As a result, there are too many opportunities for politicians to leverage their position for the benefit of themselves and those who are like them. This isn't a problem confined just to elected officials. Corporate entities are complicit in the focus shift that prioritizes the rich over the rest. In a world of corporate profit taking and the need to consistently beat last quarter's numbers, the answer to this question is the rich. Those with the greatest volume of wealth benefit the most by consolidating and maintaining their hold on financial, political, and social influence and power.

Tax benefits overtly favor the already affluent

One of the greatest indicators that point to our economic system being designed "by the rich, for the rich" is the manner by which tax policy is crafted. For consumers filing their taxes on a yearly basis, the maximization of deduction opportunities and tax breaks can be a massive boost. But for corporate taxpayers, the calculation exists on a truly different scale.

Money has long been a major influence in politics. Open Secrets notes, "As surely as water flows downhill, money in politics flows to where the power is." Pew Research Center also highlights the trouble with political finance, stating, "Americans have long believed that major political donors and special interests have too much influence on politics." 72% of participants in a 2023 survey agreed that there should be limits on the amount that individuals and organizations can spend on political campaigns. Yet, political donations consistently flow to those in a position to maintain the status quo. The result is that those with money consistently find themselves with outsized influence on how new policies are conceived and implemented.

Look at how the federal government taxes high-value individuals and companies. For example, TurboTax lobbied both the Bush and Trump administrations relentlessly to derail plans during each to introduce free filing options directly from the IRS. Under the Project 2025 plan to "simplify the tax code," a family earning $75,000 would pay three times as much via the elimination of "most deductions, credits and exclusions."

'Existing wealth' is the greatest source of continuing wealth generation

While the extremely wealthy actively pursue policy changes (or retentions) that help them keep as much money as possible for themselves, this isn't actually the most prominent feature involved in the economy's benefits for their coffers. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis reported in 2023 that 83% of the wealthiest 0.1% of the population's total lifetime income is derived from equity earnings. Compared to that of the bottom 90%, which is made up almost entirely of wage payments for labor services (80% to 90% of their income), the discrepancy is stark, to say the least. Essentially, this means that the ultra-wealthy make the vast majority of their money from their money, while the rest of the population spends their precious time working to earn a living.

The result is a divergent lived experience that sees the wealthiest Americans simply needing to budget with a bit of intelligence in order to maintain and even grow their financial fortunes. The rest, unfortunately, must work exceedingly hard to create the lifestyle they envision for themselves. Many have resorted to introducing side hustles and second jobs, a practice that can provide additional income, to be sure, but costs workers in relaxation time, the company of their loved ones, and in some cases, even their mental health.

Savings rates also account for a solid portion of the wealth gap

Underpinning the ability of a high-net-worth individual to leisurely stroll through life is the powerful utility of compound interest. The more money you have stored away in a healthy growth asset, the more extra capital you can expect to create. Compound interest is the reason why the wealthy stay that way, and in a different breath, the reason why those without great wealth find it hard to amass it. With a growth strategy in place, it would take almost eight years to save from zero to $100,000 (given a 7% yield), but just two and a half to make a savings value jump from $400,000 to $500,000.

The St. Louis Fed also found that higher rates of savings account for roughly a third of the overall wealth gap by the age of 50. This figure grows steadily from around 30 years of age and quickly surpasses even the return rate on investments by about age 35. Put frankly, those who want to accumulate plenty of wealth for themselves must start saving early, and bulk up their investment and retirement accounts with as much capital as possible. However, for those starting out with great wealth at their disposal, this practice is far easier to attain than it is for a wage earner working to make ends meet.

Wage stagnation keeps lower earners static in their financial immobility

Another stark reality facing workers is that wages have largely stagnated, leaving workers with continually weakening buying power. Since 1973, productivity among private sector workers has grown at roughly the same pace it had set in the three decades of post-war economic performance. But this year marks a distinct shift in compensation. Rather than trending alongside productivity — with more production equaling a commensurate increase in pay — as it had been since 1948, hourly compensation flatlined. It had risen by 9.2% in the 40 years that followed, compared to a productivity uptick of 74.4% (via EPI).

While 30 states have mandated a minimum wage above the federal figure, this decreed rate remains lower, when adjusted for inflation, than it was in the 1960s. Paul Krugman, writing in The New York Times, suggests that this is the direct result of a relationship outside of classical fiscal readings. "The answer [to how this might be possible] is that huge disparities in income and wealth translate into comparable disparities in political influence." Those with great wealth and power act to keep it, while seeking to create more whenever possible.

Between 1980 and 2014, the top 1% in terms of wage earnings grew their annual pay by 138% while the bottom 90% added just 15%. When taken in context with the avenues that wealthy Americans have for growing their net worth, it's clear that stagnant wages eradicate any large-scale fiscal mobility.

High-net-worth individuals and corporations alike constantly work to undermine the IRS

As mentioned previously, TurboTax has routinely lobbied the federal government to shut down IRS plans to simplify the tax preparation process for consumers. This would substantially cut into the company's profits, or perhaps even relegate it to obsolescence. TurboTax isn't alone in the practice of aggressive lobbying efforts. Both wealthy individuals and large corporations alike throw their weight around in an effort to advance friendly policy and stifle other action items that might hurt them financially. Rather than adapting to a changing world — for instance, in the context of climate change — companies seek to double down on the products and services they already offer. The thought process almost certainly pits the cost of adaptation against the price tag of lobbying to create gridlock.

Energy producers, for example, could shift their entire focus toward decommissioning fossil fuel production and replacement with renewables like wind and solar power. However, it's easier to attempt to influence policy and public perception in order to maintain the current state of affairs, so that's what they've settled on as a strategy (In the U.K., both The Guardian and the BBC have recently reported on this precise phenomenon).

The American health care conundrum: Is it a right or privilege?

Moving away from direct financial privileges that wealthy individuals enjoy, many "fringe" benefits come through the simple luck of being already wealthy. One can be found in the United States' health care system. John Oliver's "Last Week Tonight" explored components of this issue in a Season 7 episode. Specifically, Oliver warns that "our current system limits Americans' choices far more than it expands them; for starters, as a practical matter most of us don't choose our health insurance, we get what we get through our employer." The result is a labor landscape in which many Americans fear losing their job as a matter of both income generation and health coverage. This also stymies efforts to change jobs

Only recently has the conversation in the United States shifted to a more equitable model, but even the current state of affairs doesn't go as far as thinking by the U.N., which calls health care a human right, specifically. Policy and candidate language in the U.S. has started to follow this example, but in practice and tone it still lags far behind. The trouble here is that the wealthy are able to afford better health coverage, or even large out-of-pocket expenses when necessary. The rest of the country languishes with subpar insurance protections. Poor care is directly linked to worse quality of life and shorter lifespans, creating a tale of two Americas.

The 'White Collar Paradox' is alive and well on the courts' dockets

The courts tend to side with the rich, too. This has been observed and named as the "White Collar Paradox." While the court system is built to protect Americans' rights against overreach, the Supreme Court in particular has taken the position increasingly over the last five decades to protect the rights of large companies and wealthy individuals. This may be due in part to the wealthy's enhanced ability to engage in litigation, something that everyday Americans won't generally have the stomach or the cash to busy themselves with.

One important decision following this paradox came in 1973. With the San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez decision, the court overruled lower court decisions, legal scholarship, and the dominant precedent of the Equal Protection Clause and allowed states to spend more money on education for students in wealthier school districts. The result has been a better education for those in wealthier areas, at the direct expense of children who happen to be from less fortunate families. To double down on the power of campaign finance contributions, the court then did away limits on campaign contributions and expenditures a few years later with the help of truly flawed thinking that equated money with free speech (a theme in politics-focused cases that continues to be viewed through a corporate-friendly lens decades later).

Cash bail arrangements and the justice system at large grind down the less wealthy

Those of lesser economic status can't count on help from the lower courts, either. People from disadvantaged financial backgrounds are more likely to be incarcerated; the Center for Community Change reports that a full two-thirds of jailed individuals reported an annual income less than $12,000. This is partially a product of the cash bail system found in the American justice system. Once an arrest has been made, those with financial means are able to pay to be released ahead of their trial date, which could be just around the corner or end up delayed by months or years.

Poorer detainees are forced to endure confinement in jail, which can easily upend the financial lives of the individual and their loved ones. Sadder still, for those found innocent, there's no recourse available to undo these harmful effects and restore life back to the way it was. The system dismantles social, familial, and financial livelihoods in the name of overarching justice as a feature rather than an exception.

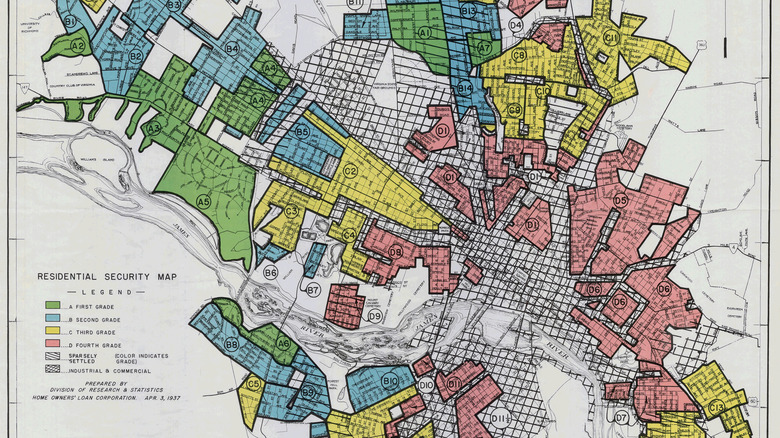

'Racial coding' sadly plays a role in this divergence of advantages, too

Returning briefly to the dichotomy of opportunities engrained in the school system, it's clear that the weight money commands goes beyond just a wealth gap issue. In communities across America, families who happen to exist within the racial minority overwhelmingly also manage to find themselves squeezed into these lesser-endowed districts. This creates a tangible segregation of students in both opportunities to learn through the inclusion of diverse voices, and in the form of financial resources that flow into educational institutions.

It's hard to quantify the entirety of damage that individual policies and decisions inflict on Black and Brown families when stacked up against one another, but the visceral effects aren't difficult to see. The reality is that our economic system disadvantages minority groups from the start, and social consciousness has been carefully curated by decades of targeted messaging into thinking that social welfare programs are an unwarranted handout rather than a valuable policy objective. Lobbying efforts have turned the narrative into a question about the habits and motivations of the people who stand to benefit from increased social programming, rather than talking about the good that these kinds of policies would do. Flip the conversation, and it's also clear that motivations and questions of "worthiness" are scarce when discussing tax breaks for corporations or enhanced incentives for wealthy individuals. This divergence is, of course, by design.

At bottom: Americans inherently understand this problematic relationship

Perhaps the most egregious feature of a system that unfailingly favors the rich is its brazenness. Everyday Americans overwhelmingly can see the system at work, and yet widespread organized dissent remains outside the grasp of those most negatively affected by its sinister mission. Pew Research Center reported in 2020 that 70% of all adults identify the U.S. economic system as "unfairly favoring the powerful interests," with just 29% considering it "generally fair to most Americans."

Similarly, the study found that 82% of Americans see "people who are wealthy" as having too much power and influence in the modern economy, while "people who are poor" saw 75% of respondents saying they had "not enough" influence. Considering the volume of Americans who are classified as "poor" (37.9 million people classified as living in poverty in 2022, or 11.5% of the population, via the U.S. Census Bureau) compared to the 735 billionaires and nearly 22 million millionaires, according to Forbes (as of 2023), the democratic process should absolutely favor them. Without collective action, however, no change is likely looming on the horizon. JT Chapman of the YouTube channel Second Thought notes that while Democratic candidates often talk about progressive issues that would shift this conversation significantly, the almost always fail to come up with major wins for poorer Americans by design — the designs of the system itself.