The Best And Worst Stock Predictions In United States History

The American stock market has provided a platform for incredible wealth generation for centuries. It's one of the most active trading space in the world, irrespective of commodity type or location, and its historical growth is truly awe -inspiring. The Philadelphia Stock Exchange was the first to emerge in the United States, forming in 1790, but the New York Stock Exchange, founded two years later, quickly became the preeminent trading forum for early American investors.

Stock markets have risen with meteoric fervor, and fallen down in spectacular fashion throughout their history. Periods of bear-market trading come and go, just as do the bull runs partially responsible for creating new fortunes. In between the market's own gyrations, stock pickers have routinely tried to best the index — often to little overarching success. Early investors might consider focusing on building a firewall against risk, utilizing index funds, ETFs, and perhaps even bonds or CDs, but this isn't the only approach to successful investing.

Large and small investors alike try to find the next big thing before it blows up, or sell shares in a big winner before its price falls back down. Some of U.S. history's most influential stock traders have seen their fair share of meltdowns and gigantic profits. These are some of the best and worst stock predictions in American trading history.

Whitney Tilson bets against Google

In 2004, Whitney Tilson wrote of Google: "I admire Google and what it has accomplished but I am quite certain that there is only a fairly shallow, narrow moat around its business." His theory was that Google — and other companies within the tech sector more broadly — was particularly vulnerable out of the natural progression of things. It had usurped Yahoo as the preeminent search engine at rapid pace, and the same thing, in Tilson's estimation, could happen to Google at a moment's notice. He famously recommended that investors steer clear of the then-search-now-everything brand ahead of its IPO. His gut feeling was that the company was overvalued, especially considering that it didn't exactly do anything concrete. A takeover by a competitor would leave Google essentially worthless as a business.

Tilson was truly and utterly wrong with his prediction, though. Google commands a 91.62% market share in the use of search engine tools, and has retained a stranglehold on the task for the last decade (dropping below 90% exactly zero times since 2014). More importantly for shareholders, perhaps, Google has become a pioneer in the world of personalized data leverage. Digital advertising has been shaped primarily by Google's hand in the era of online search, and the company has monetized the internet like no other. The brand in 2021 was worth more than 11 times its value in 2004, making Tilson's reservations about the figure a complete whiff.

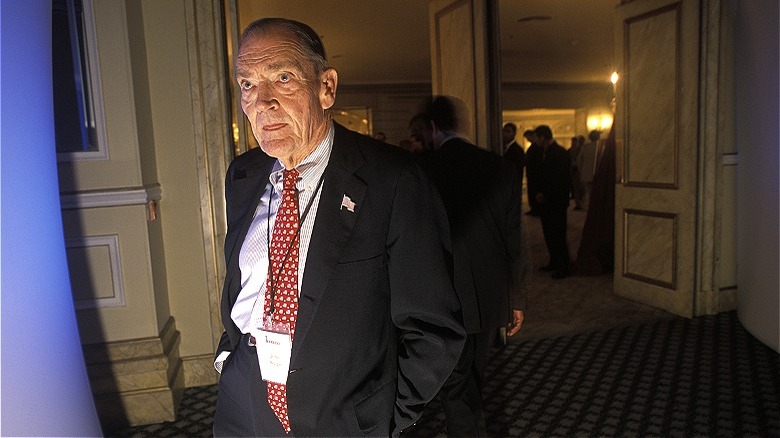

Carl Ichan's big buy in on Blockbuster

Also in 2004, one of the most disastrous high-dollar stock buys in history took place. Carl Ichan began buying up shares of Blockbuster Video, ultimately to the tune of $191 million. John Antioco, Blockbuster's CEO at the time, later wrote in Harvard Business Review that Ichan became a challenging, activist investor, who ultimately waged a proxy war for board seats and eventually created the conditions for Antioco's exit. "I didn't believe that technology would threaten Blockbuster as fast as critics thought," he noted, adding that Ichan's aversion to Blockbuster's designs on an online shift may indeed have acted as the nail in the company's coffin.

Regardless of the multiplicity of market forces that eventually killed off Blockbuster, Carl Ichan's enormous buy in of the brand left him far lighter in the wallet than he probably expected. Ichan has called the investment his worst over a career spanning more than three decades in high finance. By the time he sold his stake in Blockbuster in 2010, it had lost nearly all its value, amounting to an estimated $180 million loss.

Ichan suggested that heavy corporate debt and changes in the industry created the conditions for its demise, but it's worth noting that his buy-in came after Netflix's subscription mail service was already up and running. Moreover, Antioco suggests that the DVD model posed a greater challenge to the brand than streaming's inevitable breakout. Whatever the case, Carl Ichan's investment in Blockbuster remains a huge flop.

Bill Gates invests $150 million into Apple

In a unique twist of fate that brought two of the modern world's most influential technology companies into a union of sorts, Microsoft's Bill Gates opted to invest in its rival. Apple was on the verge of collapse in 1997, and Microsoft's $150 million investment gave it the capital it needed to continue. In exchange, Microsoft received 150,000 shares of preferred stock that would eventually convert into common shares (ultimately granting around 18 million shares when it was finally transferred completely in 2001).

This investment is unique in another way, however, operating as both a triumph in stock investing and a cautionary tale. While the millions of shares owned by Microsoft would certainly balloon into a gigantic profit, the company liquidated its stake entirely in 2003, cashing in a value of $550 million in Apple shares. If instead, the tech giant would have held onto its rival's shares, they would be worth almost $160 billion today. The profits were massive for Gates and Microsoft, but they could have been even more lucrative with a bit more patience.

Eddie Lampert invests in Sears

Eddie Lampert established ESL Investments, his own hedge fund, in 1988 after a stint at Goldman Sachs. For a time, he was highly regarded in the world of finance but that would change with his approach to Kmart and Sears. Lampert bought up droves of Kmart shares in 2003 before leveraging the company's bankruptcy proceedings to ultimately become its majority owner. He deployed a raft of cost-cutting measures that drove the company's short-term value sky high and eventually piggybacked off the financial and business fortunes of Kmart to take up control of Sears.

Both investments were ultimately doomed, and Lampert has been seemingly found out as nothing more than a mere corporate raider in both instances. Under his direction, the combined brand — Sears Holdings — lost $10.4 billion from 2013 to 2018, and numerous brand names and departments have been siphoned off or spun out from under primary control to tamp down expenditure. The result is a hollow brand that was destined for failure.

Additional reporting from Institutional Investor in 2018 dug a bit deeper into the debacle, however. It appears that during much of the restructuring under Lampert's tenure, ESL became the primary owner, or was paid commissions by investors on the movement. This means that while the pension fund was underfunded by nearly $2 billion and creditors everywhere were seeking compensation in the fallout, Lampert had potentially turned a personal profit on the joint Sears-Kmart implosion.

John Templeton buys hundreds of 'penny stocks'

John Templeton isn't a wildly well-known investor today (although his name can be found across the financial world). But his Great Depression investing strategy was both intensely lucrative and centered on a now-vaunted diversification principle. The investor bought up thousands of low-cost shares during the market's most withered years leading up to the Second World War's most intensely combative years.

In total, he purchased 100 shares in 104 different companies, all trading at $1 or less per share. This quasi-"penny stock" play provided Templeton with extreme portfolio diversity, and he held onto his investments, waiting for the market to ultimately rebound. Patience would win out here, as his $10,000 investment during the tail end of the Depression years netting him a payout four times its buy-in, selling for roughly $40,000. All the more impressive, he made his purchase in 1939 and sold his stake around the end of the war, meaning his investment doubled twice in the space of just four or five years.

His take on the market's downward trend focused on investor pessimism. He figured that the general public was too pessimistic about the fate of the industrial world, opting to cut against the grain. He's famously quoted as saying: "The time of maximum pessimism is the best time to buy, and the time of maximum optimism is the best time to sell."

Warren Buffet buys into Dexter Shoe

The "Oracle of Omaha" is renowned for his shrewd investment advice. Warren Buffett is rarely caught in a financial mistake, but that doesn't mean he's immune to them. In 1993 the investor bought Dexter Shoe, a footwear brand based in Maine, paying for the company with just over 25,000 Class A shares of Berkshire Hathaway. These stock assets have famously never been split, and are traded at over $630,000 apiece (as of early April 2024).

In exchange for Berkshire Hathaway shares, Buffett took possession of a company that he claimed "needs no fixing: It is one of the best managed companies Charlie and I have seen in our business lifetimes," he reported to shareholders in his 1993 letter. Dexter Shoe was vulnerable to the same challenge that affects all brands globally, though. It was an outfit that made high-quality goods but charged a premium for the privilege. In comparison to low-cost imports crafted in dozens of cheap overseas factories, the brand was headed for a major headache.

Buffett was correct in his short-term financial assessment of the brand, but failed to fully appreciate the devastation that domestic shoe sales would face before the decade was out. By 2007, Buffett had fully lamented the loss caused by his investment: "I gave away 1.6% of a wonderful business to buy a worthless business," he wrote in his 2007 letter to shareholders. All told, Buffett's mistake came at an opportunity cost of nearly $9 billion and counting, since it was paid for in stock rather than straight cash.

Jim Cramer goes bullish on Bear Stearns

On March 11, 2008, Jim Cramer answered a viewer's question on Bear Stearns' liquidity and stability (specifically writing to Cramer about the stock, citing it as "Bear Stearns (BSC)," rather than the bank as a financial institution). "Bear Stearns is fine," Cramer said. "Do not take your money out ... Bear Stearns is not in trouble ... Don't move your money from Bear, that's just bein' silly." Two days later on March 13, Bear Stearns became insolvent and by the weekend, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York floated a line of credit to cover its obligations and then facilitated the bank's sale to JP Morgan Chase.

Jim Cramer's call is one of his historically bad stock picks. But it's made even worse by the fact that his assertion was made on the same day that Moody's downgraded the bank's mortgage-backed securities from a B to a C rating. Days later, Cramer tried to defend his position by speaking on the bank as an institution rather than an investment asset, but the damage had already been done. Even with liquidity issues out in the open, Cramer failed to see the writing on the wall: a drop in value of over 92% in a truly precipitous value calamity.

John Bogle's index fund revolution

John Bogle (sometimes known as Jack) founded the Vanguard Group in 1974. It's a name in the investment world that even beginners will likely be familiar with. His take on the market revolutionized stock investing for large and small traders alike, and his bet on how investors would approach the market heading into the future was incredibly spot on.

Vanguard is now one of the largest investment companies in the entire world, and Bogle's primary contribution through the Vanguard brand was the concept of investing in an index rather than individual stocks. The Vanguard 500 fund was the first index fund on the market and tracked directly with the S&P 500. Rather than buying up tons of different companies, an investor could simply buy shares of Vanguard's index fund and achieve exposure to the entire portfolio on the market.

Vanguard has ridden the prominence of index investing ever since, and now manages assets worth over $8 trillion. Surprisingly, though, Vanguard itself isn't owned by Bogle or his descendants (he died in 2019). The company is owned by its own funds, which are held, bought, and sold by individual investors, so its shareholders own the firm in its entirety, closely resembling Bogle's intention of bringing the equity world closer to the everyman stock trader.

Enron fools nearly everyone

Formed in 1985 as a merger between two prior energy companies, the business did a little of everything, from power-plant construction to broadband and video-on-demand delivery. It was named America's Most Innovative Company by Fortune in 1995 and continued reaping high praise over the rest of the decade — a timeline that saw the market heading rapidly toward the dot-com bubble burst in the new century.

But beneath the surface, Enron had been deploying manipulative accounting practices shielded by mark-to-market accounting, a legitimate yet vulnerable bookkeeping method. Enron's accounting team would transfer assets and projects to other companies if they showed as a loss, keeping unprofitable business ventures off the books and off its records. The result was a continuous rise in reported profitability and a corresponding trust in the brand that was capped off by excellent share price movement.

But by August 2001, the cracks began to show and its broadband efforts reported a $137 million loss that was coupled with the resignation of Enron's CEO, Jeffrey Skilling. From there, Enron took a seismic tumble on its way down to bankruptcy and a 26-cent share price on December 2, 2001. In the years since its deception, what's leftover of the Enron enterprise has paid creditors nearly $22 billion.

Michael Burry's 'Big Short' on the real estate market

The film "The Big Short" chronicles the realization Michael Burry made surrounding the housing market. Christian Bale plays the reclusive investor and analyst who discovered that the American mortgage marketplace was headed toward a meltdown. It's a bit dire to think about, but Burry's short call on the real estate mortgage lending assets was one of the most inspired investments ever made. He discovered the trouble brewing in 2007 and took up seemingly ludicrous short positions on subprime lending products.

The market's immense destruction began in earnest a year later, and Burry eventually earned himself a profit of roughly $100 million and a windfall of $700 million for investors in his firm, Scion Capital. Since this incredibly consequential short position, Burry has continued seeking out value investments, including short calls elsewhere in the market. His most recent head-turner was a pullback from the semiconductor marketplace in the third quarter of 2023, only to drop the short position by the year's end.