Investing Rules From The 1970s That Stir Up Nostalgia In Older Boomers

Past decades have plenty to offer investors hunting for learning opportunities. The past isn't always a valuable predictor of future behavior, but it can offer some key insights about how developments tend to unfold. For instance, there's notable overlap between the economy of the 1970s compared to the present day's. For one thing, inflation was a true killer throughout the '70s, and the present moment finds itself grappling with another era of notable squeezes to the cost of living. Technological breakthroughs also birthed novel innovation in both decades: The '70s saw Intel's 4004 microprocessor hit the scene, and the first phone call on a cellular device was placed in 1973. Now, many modern investors are looking for ways to get in on artificial intelligence. While there is concern that the "AI bubble" will burst, this contemporary tech boom does bear parallels to the trends tech innovations helped guide 50 years ago.

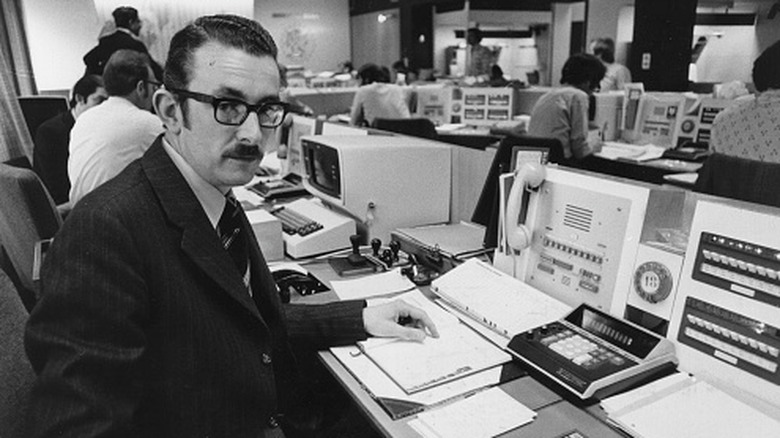

So, many of the dominant investment strategies from the 1970s may also have value today beyond the nostalgia factor that older baby boomers who actually managed finances in that period of socio-political and economic transformation might appreciate. '70s investors will remember the value of tools like bonds to combat the huge pressure of inflation. They'll also note the unique new opportunity that precious metals — specifically gold — offered. Stock market investors also spent their days in this era trying to consistently beat the market, including betting heavily on short calls. Some of these strategies have become outdated, but others may be making a comeback in the present moment.

Fight inflation with all your might

The 1970s were a time of significant economic upheaval. The 1973 oil embargo sent prices at the pump soaring and, alongside numerous other pressure points, kicked off a decade of inflation. The rate topped 5% in five separate years and broke into double digits twice (and again in 1980). The lowest inflation figure in a given year was 3.3% in 1971. Investors responded by seeking assets that had a fighting chance of at least keeping pace with the astronomical increases in the cost of living. Putting money in a standard savings account and hoping for the best was out of the question.

Today, inflation isn't nearly as daunting as the rates seen 50 years ago. But there remains a threatening affordability crisis that consumers are trying their best to beat. One option that investors sought out is perhaps a surprising port in the storm: The stock market was consistently battered during the decade, and so bonds were a valuable inflation-busting ally for investors seeking to preserve value. Investors could expect to almost break even by getting into long-term positions, especially early in the decade. That's a fairly significant feat given the astronomical downward pressure of compounding, punishing inflation figures.

Invest in gold and silver

Precious metals have long been a commodity that investors have chased. The 1970s saw the establishment of gold as a legitimate option for speculative value investing as the United States eschewed the gold standard in 1971. Since then, traders have amassed a significant volume of the stuff. The U.S. government held a gold stockpile of 261.5 million troy ounces in 2025, which was worth roughly $1 trillion as of September of that year. Meanwhile, recent surges in the price of gold and silver paired with the U.S. dollar's reduction in value have inspired swaths of individual investors to both buy and sell precious metals in 2026. The economic wreckage of the '70s similarly saw investors sprinting toward safer shores, and precious metals were a major player in that trend as well.

Today, in particular, investors seeking inroads to these assets that have continued to appreciate have a wealth of options. Gold (and silver) bullion itself is still largely seen as a solid hedge against stock volatility and inflation. Gold has seen a roughly 300% price increase over the last ten years, and silver has appreciated even faster. Importantly, investing in gold or silver doesn't have to mean working out a way to procure and safely store a large amount of physical assets. Buying into gold mining company stock and gold ETFs could bring you into the gold market while allowing another party to store physical bullion on your behalf.

Short everything you can in the stock market

The stock market as a whole saw deflated pricing action throughout the 1970s. The S&P 500 started the decade at roughly 92 points and ended at over 107. Today, the index has a value nearing 7,000. When adjusted for inflation, the value essentially halved during the '70s. As a result, some traders recommended pursuing meaningful short opportunities instead of buying into a "long position." Owning a "short" essentially means selling a stock you have borrowed because you anticipate the price going down. To do this, an investor borrows shares to sell them at the current price, then buys replacement positions to pay back the lender. If the price does drop, the short seller keeps the profits created by the difference in value.

Short selling feels like hacking the market, but it's an advanced tool that isn't kind to investors who aren't fully prepared for the risk. For those who do trade in shorts, it can open up the ability to capitalize on both the market's growth opportunities and price implosions. This inverse to standard market participation can be a whirlwind of excitement and nerves, and it harkens back to a time when short selling was a key tool to surviving two recessions (and a third entering January 1980) alongside two bear markets that dominated the decade.

Work to beat the market whenever possible

The 1970s were a time before the advent of the consumer internet, and the decade saw relatively minimal regulation to curb what has become known as insider trading. Active fund managers were able to schedule meetings with business executives, gather information ahead of public releases, and act on that knowledge with impunity. Today, this kind of behavior could land an investor in jail. In a time when information could be weaponized without fear of penalty, stock traders were incentivized to gather data, make informed decisions, and work to beat the wider market. With critical knowledge of a business' future moves, investors had a genuine ability to time a stock's momentum and get ahead of the pack.

Today, worrying about timing the market is more or less a waste of energy. "Investors as a group cannot outperform the market because they are the market," Jack Bogle, the founder of Vanguard and progenitor of the index fund, once said in a 1997 speech (via Nasdaq). Notably, Bogle's first S&P 500 indexing solution was established in 1975, right in the middle of this decade of vociferous stock picking. Today, as many as 92% of professional fund managers can't beat the market over the long term. Picking stocks can be a valuable way to provide targeted exposure, but a largely index-driven strategy is often more reliable for delivering long-term growth.